Applied Science Letters

Introduction and Objectives: Increased population of the Earth and hence increased contact among people has turned viral diseases into a major human health and medical problem. Iran is also affected by these diseases like the rest of the world. The present study aimed to investigate hantaviruses and their potential reservoirs in the world. Materials and Methods: The study was initiated through keywords searching about hantaviruses in databases, which returned 83 hantavirus-related authentic scientific articles from 1982 to 2019, out of which 60 articles were selected and studied and their data were analyzed. Results: The human hantavirus syndromes include Hantavirus Cardiopulmonary Syndrome (HCPS) and Hemorrhagic Fever with Renal Syndrome (HFRS). More than 40 species of hantavirus have now been identified, 22 of which are major public health threats. Rodents are major animal reservoirs of hantaviruses. They can spread the hantaviruses via saliva, feces, and urine. According to some reports, anti-hantavirus IgM and IgG antibodies were confirmed in people through the ELISA serological test in Iran. Studies have demonstrated that hantavirus infection existed in 10 of the 31 provinces of Iran. Conclusions: Given the presence of anti-hantavirus IgM and IgG antibodies in people in some provinces of Iran, positive cases may also exist in other provinces, which calls for further research into this serious and deadly disease. Health officials need to increase their oversight over disease monitoring.

Hantavirus Infections as Zoonotic Emerging Viral Diseases: Current Status with an Emphasis on Data from Iran

Hamid Kassiri 1, Rouhullah Dehghani 2*

1 Department of Medical Entomology, School of Health, Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences, Ahvaz, Iran.

2 Social Determinants of Health (SDH) Research Center, and Department of Environment Health, Kashan University of Medical Sciences, Kashan, Iran.

ABSTRACT

Introduction and Objectives: Increased population of the Earth and hence increased contact among people has turned viral diseases into a major human health and medical problem. Iran is also affected by these diseases like the rest of the world. The present study aimed to investigate hantaviruses and their potential reservoirs in the world. Materials and Methods: The study was initiated through keywords searching about hantaviruses in databases, which returned 83 hantavirus-related authentic scientific articles from 1982 to 2019, out of which 60 articles were selected and studied and their data were analyzed. Results: The human hantavirus syndromes include Hantavirus Cardiopulmonary Syndrome (HCPS) and Hemorrhagic Fever with Renal Syndrome (HFRS). More than 40 species of hantavirus have now been identified, 22 of which are major public health threats. Rodents are major animal reservoirs of hantaviruses. They can spread the hantaviruses via saliva, feces, and urine. According to some reports, anti-hantavirus IgM and IgG antibodies were confirmed in people through the ELISA serological test in Iran. Studies have demonstrated that hantavirus infection existed in 10 of the 31 provinces of Iran. Conclusions: Given the presence of anti-hantavirus IgM and IgG antibodies in people in some provinces of Iran, positive cases may also exist in other provinces, which calls for further research into this serious and deadly disease. Health officials need to increase their oversight over disease monitoring.

Keywords: Hantavirus, Epidemiology, Control, Distribution, Reservoirs, Prevalence, Iran.

INTRODUCTION

Viral diseases are one of the major human health and medical problems and will become more important in the future. Earth population growth has increased human contact, resulting in the easier transmission of viral diseases, some of which are a serious threat to human health. Viral diseases are very diverse; some are zoonotic in which rodents play an important role. The main viral hemorrhagic fevers whose reservoirs are rodents include Lassa fever, O’Higgins disease or Argentine Hemorrhagic Fever (AHF), Bolivian Hemorrhagic Fever (BHF), also known as Ordog Fever or black typhus, Hantavirus Cardiopulmonary Syndrome (HCPS), Hemorrhagic Fever with Renal Syndrome (HFRS). The human hantavirus syndromes include HFRS and HCPS; the latter is also called Hantavirus Pulmonary Syndrome (HPS), with related fatality mostly resulting from cardiogenic shock. HFRS is prevalent in Asian and European regions and HCPS in the Americas [1-4]. Although HCPS is a serious problem in Central and North America, most HCPS deaths and cases occur in South America [4].

In the past century, 2 important outbreaks of hantaviruses occurred in the Old and New Worlds. The first outbreak of the disease was reported during the Korean War (1950 - 1953), where more than 3000 troops fell ill with HFRS. The second outbreak occurred in the US in 1993 and was referred to as HCPS (HPS) [5]. On average, about 150000–200000 cases with HFRS per year are diagnosed throughout the globe. Nearly, 300 patients of HPS each year are diagnosed in the Americas. But, little is recognized about their circulation in the Middle East, Africa, and the Indian subcontinent. More than half of the global cases of HFRS have been reported from China [6-8].

Hantaviruses are spherical particles with a diameter of 80-110 nm. The disease was first described in South Korea in 1976. The virus is named after the name of the Hantaan River [5, 9]. Hantaviruses belong to the genus Orthohantavirus, family Hantaviridae, and order Bunyavirales. Unlike other members of the Bunyaviridae family, there is no evidence that hantaviruses were transmitted by arthropods [10-12]. The Bunyaviridae is a big family of over 350 RNA viruses. Bunyaviruses are arthropod-borne or rodent-borne, spherical, single-stranded, enveloped RNA viruses. The Bunyaviridae family is composed of a large and diverse group of RNA viruses with a tripartite genome (S, M, and L) [13, 14]. The small (S), medium (M), and large (L) segments encode the nucleocapsid protein, the glycoprotein, and the viral RNA polymerase, respectively [6, 7]. The family currently consists of five genera including Hantavirus, Tospovirus, Phlebovirus, Nairovirus, and Orthobunyavirus, which contain viruses of agricultural or medical importance. Bunyaviruses reproduce in the cytoplasm. Humans are generally dead-end hosts for Bunyaviruses except for Phleboviruses. The genus Hantavirus was described in 1983. More than 40 species of hantavirus have now been identified, 22 of which are major public health threats [6, 15, 16]. Approximately half of these species are associated with human diseases such as HFRS and HPS (also known as HCPS). Rodents, insectivores, and bats are animal reservoirs of hantaviruses, but rodents of the Muridae and Cricetidae families are the reservoirs of human pathogenic hantaviruses [15].

Hantaviruses are often associated with a rodent species. These viruses may have evolved with rodent hosts thousands and perhaps millions of years ago [5, 17, 18]. Hantavirus infection is a zoonotic disease that is transmitted from rodents to humans. Infected rodents are asymptomatic and can spread the hantaviruses via saliva, feces, and urine. Although hantavirus causes a prolonged infection in rodents, there is a period of 3-8 weeks after the primary infection that the rodent releases or excretes the most viral particles [19]. Virus aerosols are the main means of transmission of infection to humans, as accidental hosts, and enter the body through respiration. In addition, bite of infected rodents or exposure of damaged skin or mucous membranes to rodent secretions are alternative transmission ways. Although very rare, human-to-human transmission has been reported for the Andes virus in hospitals in South America [20].

The disease risk factors are unknown; however, people with lower socioeconomic status and those engaged in activities that expose them to rodents are at a greater risk of infection [21, 22]. Risk factors for hantaviruses infection usually include involvement in outdoor activities such as village and forestry work and military training exposing people to dust contaminated by rodents [23]. Soldiers, farmers, and village residents are at a high risk of hantaviruses. It is now known that some hantaviruses can exist in many urban areas of the world [5].

Like other viral diseases, hantavirus is one of the dangerous diseases in which rodents are both reservoirs and vectors. The mortality rate of the Old World Hantavirus (HFRS) ranges from <0.1% for the Puumala virus to about 5-10% for the Hantaan virus. The fatality rate of the New World Hantavirus (HPS or HCPS) is 40% up to 60% in some outbreaks [7, 21]. In a review study, Jonsson et al. showed that the overall fatality rate of hantaviruses in humans is up to 15% and 50% for HFRS and HCPS, respectively [5].

Rodents are widely distributed and diverse in Iran, and many rodents of the Muridae and Cricetidae families, introduced as the reservoirs of the human pathogenic hantaviruses worldwide, are also living in Iran [15, 24-27]. On the other hand, serological and molecular methods have confirmed hantaviruses as the cause of an emerging zoonotic disease in recent years in Iran [8, 28, 29], which may increase in the coming years. In attention to the possibility of hantaviral outbreaks, further research is needed to investigate the epidemiology and ecology of hantaviruses. Therefore, Iranian health authorities should be constantly on the lookout for an outbreak or epidemic. Given the particular importance of this disease in terms of health/medicine, and since it has attracted attentions in Iran and worldwide, the present study was conducted to evaluate the current status and epidemiology of hantaviruses in the world, particularly in Iran.

MATERIALS ANS METHODS:

The ethical principles of this study were evaluated and discussed in the ethics committee of the Deputy of Research, Social Determinants of Health Research Center, Kashan University of Medical Sciences, and after making needed modifications, it was approved. The study was performed under the provisions of the Helsinki Declaration.

This was a review involving keyword search for hantavirus, epidemiology, hemorrhagic fever, rodents, reservoirs, control, global spread, symptoms, treatment, and prevention in online sources, websites of high-impact health and medical journals, and scientific databases such as the Web of Science, Ovid, PubMed, Systematic Review, Scirus, Science Direct, Scopus, Google Scholar, and Medline during 1982-2019. A total of 83 articles were found and 60 articles were selected considering the study objectives. Finally, the status of hantavirus infection in the world and Iran was investigated. The findings were presented in the form of a review article and its provincial distribution map in Iran was prepared. In addition, the reservoir importance, role in disease transmission, frequency in Iran, as well as the control and prevention methods were analyzed.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

As an emerging zoonotic viral disease, hantaviruses cause HFRS in Asia and Europe and HCPS in North and South America. Hantaviruses are generally mentioned as New World and Old World hantaviruses because of the kind of disease that appears in humans and the geographic distribution of their reservoirs [5]. The worldwide distribution of rodents, as the major reservoirs of hantaviruses, provides great potential for hantavirus outbreaks. There is a great concern about public health in different continents where rodents of Muridae and Cricetidae families exist. Therefore, the disease can be transmitted and spread throughout the world [30].

Favorable environmental conditions such as mild winters, summer rainfalls, abundant habitats, poor environmental health, and poor sanitary waste disposal can greatly increase the rodent population. Rodents are mostly found in rural areas and busy urban areas [31]. They can easily continue their activities and meet their nutritional needs in human residential areas or hospitals; therefore, the prevalence of hantavirus infections in the world is not unexpected [32, 33]. Wild rodents may enter human settlements in rural areas [34], and humans may become infected through inhalation of virus particles in the air and direct contact with infected rodents, as well as their saliva, feces, and urine , as well nests. Hunter animals such as cats, dogs, jackals, and wolves may become infected through contact with infected rodents. But it is unlikely that the virus can also be transmitted to other animals or humans. Domestic animals may put infected rodents in contact with humans [19]. Hantavirus is transmitted to rodent reservoirs through horizontal transmission, i.e. aggressive and competitive behavior, biting, and close contact [28, 31]. During an outbreak in the United States, 30% of trapped rats were infected, most of whom were adult males. This can be attributed to their competitive and offensive behavior [35, 36].

Most of the times, symptoms happen 9 to 33 days after the hantavirus enters the human body, but symptoms may emerge as late as eight weeks or as early as one week. Early symptoms of HFRS can include nausea, headache, chills, back pain, abdominal pain, fever, blurred vision, flushing of the face, rash and redness, or inflammation of the eyes. Late symptoms may include vascular leakage, acute shock, low blood pressure, acute kidney failure, and severe fluid overload. Viral infections of Puumala, Seoul, and Saaremaa are generally milder. However, viral infections of Hantaan and Dobrava generally cause severe symptoms. Full recovery may last weeks or months. Initial symptoms of HCPS include muscle aches, fever, fatigue, dizziness, headaches, chills, vomiting, abdominal pain, nausea, and diarrhea. Late symptoms of HCPS include coughing, shortness of breath, and finally, the lungs fill with fluid [37-40].

Hantavirus infection can cause significant mortality and morbidity in humans. 3 major clinical syndromes can be distinguished following hantavirus infection: HCPS, which can be caused by Sin Nombre (most infections are caused by Sin Nombre virus), Andes, Bayou, Black Creek Canal, Monongahela, New York; and HFRS, mainly caused by Saaremaa, Seoul, Hantaan, Puumala, and Dobrava viruses; Nephropathia Epidemica (NE), a mild form of HFRS caused by Puumala virus. The disease has been reported in Turkey, Iran’s neighboring country [8, 37, 40-44].

There is no specific vaccine for hantaviruses. There is no antiviral medicine approved for treating this disease. Supportive therapy is a key component of care. Rapid admission to the intensive care unit is insured as the disease is presumably to progress. Consider early intubation, blood pressure levels, any secondary infection, dialysis, and oxygen supplementation. Because of fast fluid changes, attention must be attended to the patient’s fluid and electrolyte balance level in intensive care units. Intravenous ribavirin, as an antiviral drug, reduces disease and death associated with HFRS if used very early in the illness. It should be considered that the majority of human hantavirus infections have no obvious clinical symptoms. This character makes the recognition of hantavirus infections hard, especially in areas where the infection is not endemic. Serological tests are the main laboratory diagnostic tools of hantavirus infections. These tests detect IgG and/or IgM antibodies against hantaviral antigens in serum. Antigen detection through the method of reverse transcriptase PCR with specific primers is useful for the diagnosis of the disease. Indirect IgG and IgM Enzyme-linked Immunosorbent Assays (ELISAs), also IgM capture ELISAs are the most common and trustworthy serological assay for hantavirus infections [8, 37, 38, 45, 46].

Hantavirus can cause a mild or severe disease with a mortality rate of up to 35%. Both clinical forms of HFRS and HCPS are associated with acute thrombocytopenia and changes in vascular permeability, and may include symptoms in kidneys and lungs. However, the Old World Hantavirus Syndrome (also known as HFRS) mainly affects kidneys, whereas the New World Hantavirus (also known as HCPS) is predominantly associated with heart and lung failure [47-50].

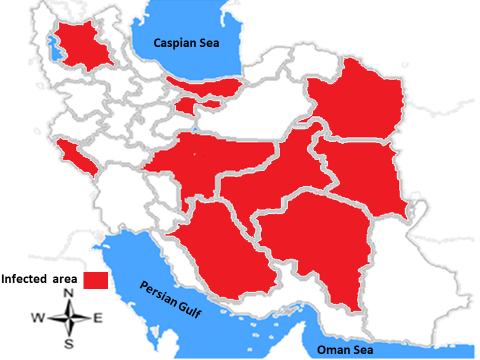

Reports of hantaviruses in Iran date back to 1982. The report, which deals with the status of hantavirus strains in Europe and East Asia, identifies Iran as one of the areas where anti-hantavirus antibodies have been reported in humans [51]. To find hantavirus evidence in Iran, 10 serum samples of patients with thrombocytopenia and acute renal failure were collected from Imam Hossein Hospital in Tehran City (northern Iran) from 2008 to 2009. Whole samples were tested by Immunofluorescent assay (IFA) for antibodies against hantavirus, nevertheless, no seropositive patients were detected. Thereafter, the hantavirus infection was confirmed in Iran in 2013. The infection was reported in street sweepers in the center of the country. In this study, serological and molecular tests confirmed the presence of hantavirus infection, and the abundance of rodents in their workplace was identified as a key risk factor due to the positive test [8]. In a study by the Pasteur Institute of Iran during 2014-2016, 113 serum samples were collected from 25 provinces of Iran. The samples were analyzed for hantavirus infection through IgM/IgG ELISA and pan-hantavirus RT-PCR tests. The virus genome was not found in the samples, but IgM and IgG were detected in 19 and 4 samples, respectively [29]. IgM and IgG immunoglobulins were detected in Tehran, East Azarbaijan, Razavi Khorasan, Mazandaran, Isfahan, Kerman, Fars, South Khorasan, Yazd, and Ilam Provinces of Iran (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Geographical distribution of Hantavirus based on the diagnosis of IgM and IgG immunoglobulins in different provinces of Iran

Health care workers and physicians do not have sufficient knowledge about this infection. Therefore, it is counseled to direct seroepidemiological studies in rodents and humans in different geographical areas of Iran until recognizing risk factors and the precise position of Hantavirus infection [51].

This study confirmed previous reports of hantavirus in Iran [37]. Reports indicate that there is a human infection in Iran. Just a few minutes of exposure to the urine, feces, and saliva of infected rodents is enough for being affected. As mentioned earlier, infection is most likely to occur when dried particles of urine, feces, and saliva of infected rodents are inhaled or come in direct contact with lesions or the eye or mouth mucosa. Infection can also enter the body through the consumption of contaminated water and food. In HPS, humans can be infected by infected rodent bite. There is also a risk of being infected by the manipulation of infected rodents’ burrows [5, 52].

There are approximately 79 species of rodents in 31 genera and 8 families throughout Iran [53-55]. Rodents are one of the main public health pests and can keep or transmit a large number of pathogens in various ways [42-46], causing major health and medical problems for humans. However, the abundance and distribution of rodents living in natural habitats or within urban and rural residential areas certainly increase their importance in the field of health. Therefore, it is necessary to control their population [56-60].

CONCLUSIONS:

Given that hantavirus IgM and IgG immunoglobulins have been reported in various provinces of Iran, there may be positive cases across the country; this necessitates further research on this important disease. Health authorities should increase their surveillance on the disease in the country. On the other hand, the plenty and distribution of rodents in Iran, change and manipulation of the environment, construction of rural residential areas due to increased population, agricultural expansion and influencing the rodents’ natural habitats, and non-compliance with environmental health tips are among the factors that can increase human contact with the disease reservoirs. Mismanagement can result in outbreaks or extensive epidemics of hantaviruses. Therefore, health managers should increase awareness about disease transmission. In addition, the Iranian Department of Environmental Protection should enhance its monitoring to prevent the manipulation of nature and wildlife.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS:

The authors would like to thank the Research Health vice-chancellery of Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences, Ahvaz, Iran and Kashan University of Medical Sciences, Kashan, Iran for their cooperation.

Conflict of interest statement:

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Financial disclosure:

There were no sources of extra-institutional commercial findings.

Funding/Support:

This research did not receive any specific grants from any funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Authors’ contribution: All authors participated in the research design and contributed to different parts of the research.

REFERENCES

Kassiri H. Bionomics of phlebotomine sand flies (Diptera: Psychodidae) as vectors of leishmaniasis in the County of Iranshahr, Sistan-Baluchistan Province, Southeast of Iran. Iran J Clin Infect Dis. 2012;6(3):112–6.28.