Applied Science Letters

Background: Acute viral gastroenteritis is a major source of morbidity and mortality in young children. The purpose of the study was to investigate the frequency and cause of acute gastroenteritis in children admitted to the Ilam hospital in Iran. Materials and Methods: 103 children suffering from acute diarrhea suspected of viral infections were included. Stool samples were collected and the prevalence rate of common viruses such as Rotavirus, Norovirus GI/GII, Astrovirus, Sapovirus, Adenovirus (multiplex) Picornavirus, Picobirnavirus, Torovirus, Bocavirus, and Coronavirus was determined by multiplex PCR- based, and Monoplex assay. Results: The viruses that cause the symptoms, were detected in 37 out of the 103 cases, that 2 cases were found to be co-infection. Rotavirus was detected in 17/103 Norovirus, in 13/103, Astrovirus, in 4/103, and Adenovirus, in 3/103. The percentage of Norovirus genogroups I and II were 15.4% and 84.6%, respectively.We could not detect any virus in winter. Conclusions: The viral etiology was confirmed in about one-third of the subjects. Rotavirus was the most frequently detected virus.

Prevalence and Seasonal Frequency of acute viral gastroenteritis in children less than 5 years in Ilam, Iran

Jasem Mohammadi1, Razieh Amini2, Akbar Akbari3, Mansour Amraei4, Shahab Mahmoudvand5, Farid Azizi Jalilian6*

1Department of Pediatrics, Faculty of Medicine, Ilam University of Medical Sciences, Ilam, Iran.

2Department of Molecular Medicine and Genetics, Faculty of Medicine, Hamedan University of Medical Sciences, Hamedan, Iran.

3Abadan School of Medical Sciences, Abadan, Iran.

4Department of Physiology, Faculty of Medicine, Ilam University of Medical Sciences, Ilam, Iran.

5Department of Medical Virology, Faculty of Medicine, Hamedan University of Medical Sciences, Hamedan, Iran.

6Department of Medical Microbiology, Faculty of Medicine, Ilam University of Medical Sciences, Ilam, Iran.

ABSTRACT

Background: Acute viral gastroenteritis is a major source of morbidity and mortality in young children. The purpose of the study was to investigate the frequency and cause of acute gastroenteritis in children admitted to the Ilam hospital in Iran. Materials and Methods: 103 children suffering from acute diarrhea suspected of viral infections were included. Stool samples were collected and the prevalence rate of common viruses such as Rotavirus, Norovirus GI/GII, Astrovirus, Sapovirus, Adenovirus (multiplex) Picornavirus, Picobirnavirus, Torovirus, Bocavirus, and Coronavirus was determined by multiplex PCR- based, and Monoplex assay. Results: The viruses that cause the symptoms, were detected in 37 out of the 103 cases, that 2 cases were found to be co-infection. Rotavirus was detected in 17/103 Norovirus, in 13/103, Astrovirus, in 4/103, and Adenovirus, in 3/103. The percentage of Norovirus genogroups I and II were 15.4% and 84.6%, respectively.We could not detect any virus in winter. Conclusions: The viral etiology was confirmed in about one-third of the subjects. Rotavirus was the most frequently detected virus.

Keywords: Gastroenteritis, Rotavirus, Norovirus, Astrovirus, Adenovirus.

INTRODUCTION

Acute gastroenteritis (AGE) is the second leading cause of preventable illness in children younger than 5 years of age, which has been reported as a major cause of high morbidity and mortality rates. [1] Every year more than two billion diarrhea cases occur among children under 5 years of age, worldwide. [2] Globally, diarrhea causes more than 1 million deaths worldwide. Moreover, nearly half-million deaths occur annually as a result of this disease and make it as the fourth cause of death in children younger than five years old all over the world. [3, 4]

AGE is a major source of mortality, especially in developing countries. However, in developed countries, mortality is low, but morbidity and the economic consequences of this infection is significant. [5] Risk factors for infectious gastroenteritis are including poor hygiene, unsanitary water and contaminated food. [6]

Several enteric infectious agents, including bacteria, parasites, and viruses, are responsible for AGE disease. [2] Many studies have shown that a causative organism was identified in approximately 50% of cases. [7] Furthermore, it was reported that viruses, bacteria, and parasites were identified in∼70%, 10-20% and <10% cases, respectively. [2]

In worldwide, enteric viruses have been recognized as the most significant etiological agents of the disease. Based on a report from the Center for Disease Control, gastroenteritis infection caused by viruses can cause more than 200,000 deaths of children per year worldwide. [8, 9] Rotavirus, norovirus, astrovirus, and adenovirus are the recognized major viral etiologies of diarrheal illness with rotavirus being a leading cause. [4, 10, 11]

Of these viral agents, species A Rotavirus was the most prevalent cause of viral gastroenteritis in children under 5 years of age. [12] Moreover, other enteric viruses including Norovirus, enteric Adenovirus, Astrovirus have been reported as the most significant etiological agents of childhood viral gastroenteritis. It was recently reported that Bocavirus, human Parechovirus, human Picobirnavirus, and Torovirus may be associated with gastrointestinal infections in pediatric and adult patients. [1, 5, 13]

Rotaviruses are the most common cause of about 20–50% of diarrheal infections and >450,000 deaths annually, worldwide. [7] Despite widespread utilization of the vaccine in developed countries, rotavirus remains the leading cause of childish diarrheal illness worldwide. According to the Centers for Disease Control estimation, there were still 215,000 rotavirus-related deaths in 2013. [9]

It has been shown that Noroviruses are also the second cause of acute infantile gastroenteritis in countries after the introduction of universal rotavirus vaccination so that seroepidemiologic studies showed that 50-90% of children younger than 2 years of age have antibodies to Noroviruses. Since the arrival of the rotavirus vaccine in the market, norovirus has become the most common cause of viral gastroenteritis in the United States. And according to CDC, norovirus is known to be involved in 19 to 21 million total illnesses annually. It is also estimated to cause 56,000-71,000 hospitalizations and 570-800 deaths per year in the United States. [9] Worldwide, the most common norovirus genotype is GII.4 which is responsible for several outbreaks. Currently, Researchers have shown that certain enteric Adenoviruses are an important cause of infantile acute diarrhea. Analysis of recent studies confirmed that they cause 2-6% of gastroenteritis cases. [14] Human Astroviruses infection also have been increasingly identified as an important agent of gastroenteritis in both developing and developed countries which reported in nearly 2%-9% of cases. [15]

In Iran, in a study performed by Shoja et al, detection rates of Rotavirus, Norovirus, Adenoviruses, Sapovirus, and Astrovirus between 1986 and 2011 in children with acute gastroenteritis were 39.9%, 6%, 5.7%, 4.2%, and 2.7%, respectively. [16] Also, Monavari et al reported bocavirus isolation from 8% children with AGE. [17]

This is a cross-sectional study aimed to identify the frequency of enteric viruses such as Rotavirus, Norovirus, enteric Adenovirus, Astrovirus, Bocavirus, Picobirnavirus, Coronavirus, and Torovirus, in fecal specimens collected from children less than or 5 years of age who referred with acute diarrheal diseases to Ilam hospitals.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Sample Collection

This cross-sectional study has been done in the Ilam province from March 2015 to March 2017. Stool samples that already screened and included to consider for detecting viral infectious agents (N=103), were collected from patients with acute gastroenteritis. Initially, the samples were examined by culture using Blood Agar, Xylose Lysine Deoxycholate Agar (XLD) and three different wet mount procedures (normal saline and Lugol and methylene blue) for detection of bacteria and parasitic life forms. The negative samples (N=103) were considered for viral investigation. In this step, briefly, stool specimens were prepared by diluting 0.5 gr of stool in 9.5 ml of PBS (Phosphate –buffered Saline). The resulting suspension was subjected to a vigorous vortex (15 sec) and then centrifuged (at 10 min at 4000 RPM). The supernatant was passed through a 0.45um syringe filter (Jetbiofil, China) and stored at -70°C until use.

Viral nucleic acid extraction

Viral nucleic acid extraction from 200 ul of the supernatant was performed using a Viral Gene-SpinTM kit (iNtRON Biotechnology, INC, Seoul, Korea). Extractions were carried out according to the manufacturer's instructions. Extracted viral nucleic acid stored at -20°C until use.

Monoplex and Multiplex PCR

The reaction is carried out with an initial cDNA synthesized using Revert Aid First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Thermofisher, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. PCR was performed using published primers (Table 1) for Picornavirus, Picobirnavirus, Torovirus, Bocavirus, and Coronavirus individually, at 95◦C for 15 min, 35 cycles of amplification (30 sec at 94◦C; 30-45 sec at different annealing temperature depend on type of virus ◦C; 45-60 sec at 72◦C), and a final extension step at 72◦C for 10 min in a Veriti, HID, 96 well thermal cycler (Applied Biosystems, USA) and the amplified viral nucleic acid products were detected by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis. Rotavirus, Norovirus GI/GII, Astrovirus, Sapovirus, Adenovirus detected by a multiplex real-time method that using Fast Track Diagnostics (FTD) viral gastroenteritis multiplex PCR detection kit (FTD, Luxembourg), according to the manufacturer’s instructions, and was carried out using Roche LC96 (Roche, USA) real-time PCR.

Table 1. Primers sequences and characteristics.

|

1 |

Picornavirus |

F: CATTCAGGGGCCGGAGGA |

297 bp |

|

|

Timo H, et al.1989.(43) |

R: AAGCACTTCTGTTTCC |

Tm:50(°C) |

|

2 |

Picobirnavirus |

F: TGGTGTGGATGTTTC |

200bp |

|

|

Martínez LC, et al.2003.(44) |

R: ARTGY TGGTCGAACTT |

Tm: 45(°C) |

|

3 |

Torovirus |

F: TAATGGCACTGAAGACTC |

219bp |

|

|

Duckmanton L, et al. 1997. (45) |

R: ACARNATAACATCTTACATGG |

Tm:51(°C) |

|

4 |

Bocavirus |

F: CGCCGTGGCTCCTGCTCT |

570 bp |

|

|

Jun S, et al.2013.(46) |

R: TGTTCGCCATCACAAAAGATGTG |

Tm:59(°C) |

|

5 |

Coronavirus |

F: ACWCARHTVAAYYTNAARTAYGC |

251bp |

|

|

Vijgen L , et al.2008.(47) |

R: TCRCAYTTDGGRTARTCCCA |

Tm:48(°C) |

Statistical analysis

The outcomes for all tests were analyzed by using SPSS version 20. To determine categorical parameters were used the Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test. Statistical significance was defined at P < 0.05.

Ethical considerations

This experimental study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Ilam University Medical Science with approval ID (IR.MEDILAM.REC.1397.64) and also, the statement on informed consent from the parents of participants provided in the manuscript as Stool samples were collected from children’s under 5 years in the study.

RESULTS

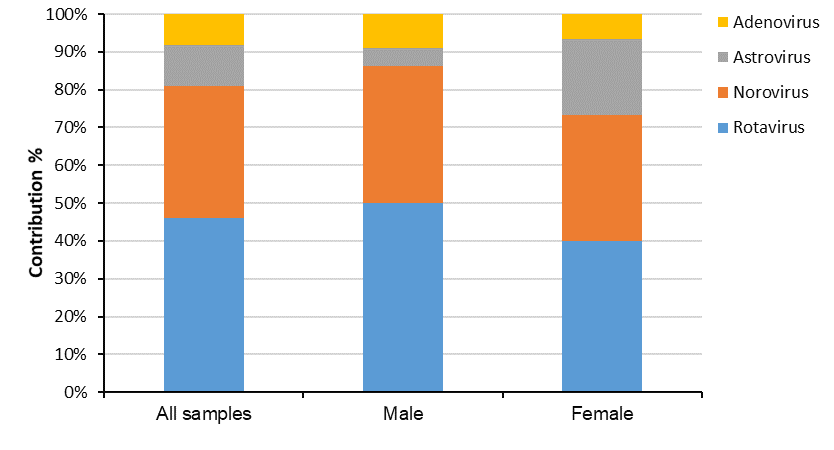

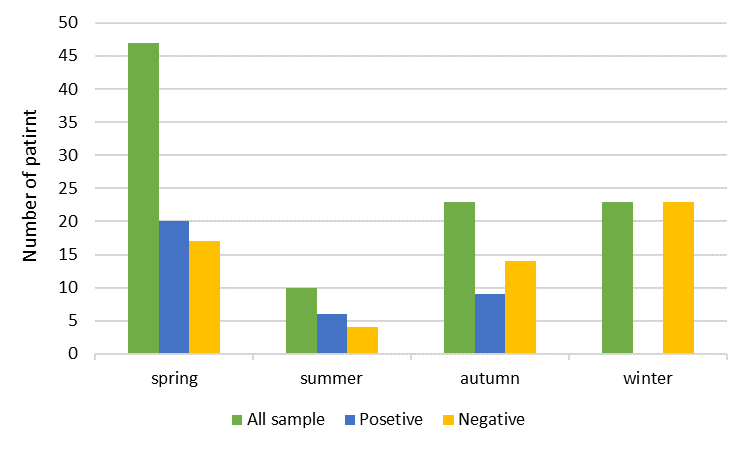

Out of 103patient with acute gastroenteritis who were included in this study, 57 (55.33%) were male and 46 (44.66%) were female (Figure 1). Overall, the viral pathogen was detected in 37 of the 103 total samples (35.92%). Rotavirus was detected in 17/103 (16.50%) (Male: 11/103, 10.67%; Female: 6/103, 5.8%); Norovirus, in 13/103 (12.62%) (Male: 8/103, 7.76%; Female: 5/103, 4.85%); Astrovirus, in 4/103 (3.88%) (Male: 1/103, 0.97%; Female: 3/103, 2.91%); and Adenovirus, in 3/103 (2.91%) (Male: 2/103, 1.94%; Female: 1/103, 0.97%) of subjects. Sapovirus, Picornavirus, Picobirnavirus, Torovirus, Bocavirus, and Coronavirus were not detected in any of the cases. The percentage of Norovirus genogroups I and II were (2 patients) 15.4% and (11 patients) 84.6%, respectively. Out of the total 103 subjects, 47 (45.63%), 10 (9.70%), 23 (22.33%) and 23 (22.33%) cases were collected in spring, summer, autumn and winter seasons, respectively (Figure 2). Of the 37 positive subjects, Rotavirus, Norovirus, Astrovirus, and Adenovirus were detected in spring (20 of the 47 samples, 42.55%), summer (6 of the 10 samples, 60%), autumn (9 of the 23 samples, 39.13%), but not winter (0 of the 23 samples), respectively. According to the multiplex PCR results, from a total of the 37 positive samples, 2 cases were found to be co-infection. Interestingly, Noro/Rota and Astro/Rotavirus co-infection were observed in 1 (2.85%) and 1 (2.85%) of the cases, respectively.

Figure 1: Frequency of sex distribution of the detected gastroenteric viruses in stool collections from the children under 5 years old admitted in Ilam Hospital, Iran, 2013 to 2015.

Figure 2: Seasonal distribution of viral gastroenteritis in children under 5 years old hospitalized in Ilam Hospital, Iran, 2013 to 2015.

In this study, Rotavirus, Norovirus, Astrovirus, and Adenovirus were detected in spring (20 of the 47 samples, 42.55%), summer (6 of the 10 samples, 60%), autumn (9 of the 23 samples, 39.13%), but not winter (0 of the 23 samples). We could not detect any virus in the winter which could be because of fewer samples, circulation of different viruses or other etiological agents that are not included in this study. The highest prevalence of Rotavirus (4 of the 10, 40%), Norovirus (2 of the 10, 20%) and Astrovirus (1 of the 10, 10%) infections were identified in summer, followed by spring (Rotavirus; 8 of the 43, 19.14%, Norovirus; 8 of the 47, 17.02% and Astrovirus; 2 of the 47, 4.25%) and autumn (Rotavirus; 4 of the 23, 17.39%, Norovirus; 3 of the 23, 13.04% and Astrovirus; 1 of the 23, 4.34% ) and the lowest in winter (0 of the 23) (Table 2).

Table 2. The number of samples tested, positivity rates and viral findings by season.

|

|

Spring |

Summer |

Autumn |

Winter |

Coinfection |

||||

|

Male |

Female |

Male |

Female |

Male |

Female |

Male |

Female |

|

|

|

Total sample |

25 |

22 |

6 |

4 |

12 |

11 |

14 |

9 |

2 |

|

Pasetivity, (N %) |

13 52% |

9 40.9% |

3 50% |

3 75% |

5 41.6% |

4 36.36% |

0 0% |

0 0% |

|

|

Identified viruses |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Rotavirus |

6 24% |

3 13.6% |

2 33.33% |

1 25% |

3 25% |

2 18.18% |

0 0% |

0 0% |

1samle with Astrovirus 1sample with Norovirus |

|

Norovirus |

5 20% |

3 13.6% |

1 16.66% |

1 25% |

2 16.66% |

1 9.09% |

0 0% |

0 0% |

1sample with Rotavirus |

|

Astrovirus |

1 4% |

1 4.5% |

0 0% |

1 25% |

0 0% |

1 9.09% |

0 0% |

0 0% |

1sample with Rotavirus |

|

Adenovirus |

1 4% |

2 9% |

0 0% |

0 0% |

0 0% |

0 0% |

0 0% |

0 0% |

|

DISCUSSION

Acute gastroenteritis is known as a global public health issue caused by different enteric pathogens (various bacteria, viruses, and parasites), which causes high rates of morbidity and mortality worldwide, especially in developing countries, among children under five years of age. [1, 5] It is estimated, that acute gastroenteritis occurs with about 1.5 billion cases of diarrhea yearly in the Eastern Mediterranean Region countries, resulting in 65,000 deaths. [2, 18] Enteric viruses, such as Astrovirus, human Adenoviruses and especially species A Rotaviruses and Noroviruses have been reported as the important causes of acute gastroenteritis. [5, 12]

In the present survey, we have examined the prevalence rate of Rotavirus, Norovirus, Astrovirus, Sapovirus, Adenovirus, Picornavirus, Picobirnavirus, Torovirus, Bocavirus and Coronavirus infections among the children under 5 years with acute gastroenteritis during March 2013 to March 2015. Specimens were tested and the viruses were found in 33.98% (37 of 103) of the cases.

Based on the reports from WHO in 2012 and 2015, the global evaluation of childhood deaths is caused by rotavirus infection during 2008 and 2013, respectively. In Iran, rotavirus is involved in about 2000 deaths in 2008 and 270 deaths in 2013. [19-21]

In the current study, rotaviruses were detected in 17 of the 103 patients (16.5%) with acute gastroenteritis, which is comparable to the results of Shoja et al. [16], and less than Moradi-Lakeh et al. [22], and Kargar et al. [23], who reported, 11.36%, 79%, and 28.37% of Rotavirus infection in different regions of Iran, respectively. In other countries, the rotavirus prevalence rate has been reported as 13 to 40% of all cases of gastroenteritis. [24-27] The differences in the prevalence rates among various studies may be related to different methods used for the detection of Rotavirus, geographical differences, sample size, and cultural differences. For instance, in comparison with molecular methods, serologic assays cause more false-positive results, which in many studies have been shown. [26, 28, 29] In Azaran et al. study, Rotavirus antigen detected by the ELISA method was reported as 50%, while 36.5% of samples were found positive by RT-PCR. [8] Moreover, in a study conducted by Alam et al. the frequency of Rotavirus measured by PCR in 89 EIA positive samples was found as 44 (49.43%) of the 89. [29] Our findings also demonstrated, that there were no significant differences in the rate of Rotavirus detection between the male (11 of the 57, 19.29%) and the female subjects (6 of the 46, 13.04%) (P=0.43). These findings were in agreement with that of another similar study. [30]

Noroviruses are important causes for non-bacterial gastroenteritis, with a prevalence rate of 6%-19% worldwide. [30, 31] In the current study, Noroviruses were detected in 13 of the 103 (12.62%), which is consistent with the results reported by other studies in Iran. [32-35] These results are also in accord with those reported in previous studies in other countries. [36-38] The prevalence rate of Norovirus detection in males and females was 14.03% (8 of the 57) and 10.86% (5 of 46), respectively (P=0.76). Also, the result has shown, among the 13 Norovirus-positive cases, 2 (15.38%) and 11 (84.6%) related to genogroups GI and GII, respectively. This finding supports the previous studies, regarding Norovirus genogroup GII is more common than Norovirus GI. [30-34]

Astrovirus is a viral causing of gastroenteritis, which has been reported in up to 10%-30% of sporadic gastroenteritis. In our study, Astrovirus was detected in 4 of 103 (3.88%) cases, which almost was comparable with the results of previous studies in Iran and other countries. [39-42] In other studies, the prevalence rate of Astrovirus was higher than our study. [43-45] Several studies reported a low prevalence rate of Astrovirus, while others reported a high prevalence rate. This controversy may come from the differences in the quality of samples (the decay of viral RNA in samples due to repeated thawing and freezing), low viral load in samples, sensitivity methods to detection, the prevalence rate in different areas and the condition of samples maintenance. Although the frequency of Astrovirus was higher in samples from females (3 of the 46, 6.25%) than males (1 of the 57, 1.75%), the difference was not statistically significant (P=0.32).

In most countries, Adenoviruses are leading causes of viral diarrhea and have due to noticeable deaths in children. In this survey, the prevalence rate of Adenovirus was 3/103 (2.91%) cases. This result corresponds with other studies performed in Iran, Indonesia, Brasil. [41, 46, 47] But this finding conflicts with the findings of studies conducted in Iran and Italy. [48, 49] In our study, significant differences did not observe between the prevalence of Adenovirus in males (2 of the 57, 3.50%) and females (1 of the 46, 2.17%) (P=1.00).

In the present paper, co-infections with Rota/Noro and Rota/Astro viruses were observed in 1 (2.85%) and 1 (2.85%) of the 37 positive cases, respectively. Studies reported co-infections with Rota/Norovirus at frequencies ranging from 1-50%, [47, 49] which is comparable to our results. Furthermore, in previous studies, Rota/Astro virus co-infection has been reported. [50] In our survey, Rota/Astro virus co-infection was also detected in 1 of the 103.

CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, our finding on Rotavirus, Norovirus, Astrovirus, and Adenovirus almost corresponds with the other studies that were done in Iran. We could not detect Picornavirus, Picobirnavirus, Torovirus, Boca virus, Coronavirus, and Sapovirus which is most probably due to a low number of samples. On the other hand, we had 66 negative results for our panel of viruses which suggest that it is necessary to consider the new and different causative infectious agents especially new viruses in future studies.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The study was supported by Vice-chancellor for Research and Technology, Ilam University of Medical Sciences (Project no.: 9304242115).

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

REFERENCES